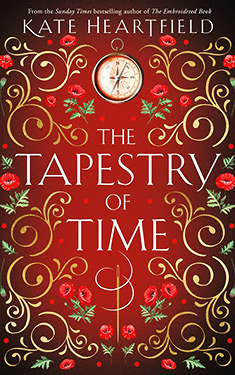

The Tapestry of Time

| Author: | Kate Heartfield |

| Publisher: |

HarperCollins/Voyager, 2024 |

| Series: | |

|

This book does not appear to be part of a series. If this is incorrect, and you know the name of the series to which it belongs, please let us know. |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Historical Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

Love, heroism and the supernatural collide in the midst of war.

There's a tradition in the Sharp family that some possess the Second Sight. But is it superstition, or true psychic power?

Kit Sharp is in Paris, where she is involved in a love affair with the stunning Evelyn Larsen, and working as an archivist, having inherited her historian father's fascination with the Bayeux Tapestry. He believes that parts of the tapestry were made before 1066, and that it was a tool for prediction, not a simple record of events.

The Nazis are also obsessed with the convinced that not only did it predict the Norman Conquest of England, but that it will aid them in their invasion of Britain.

Ivy Sharp has joined the Special Operations Executive -- the SOE -- a secret unit set up to carry out espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance. Having demonstrated that she has extraordinary powers of perception, she is dropped into Northern France on a special mission.

With the war on a knife edge, the Sharp Sisters face certain death. Can their courage and extrasensory gifts prevent the enemy from using the tapestry to bring about a devastating victory against the Allied Forces?

Excerpt

Halfway between the Louvre and the canteen for Nazi soldiers, Kit becomes uneasy. Like cold fingers fumbling up her arms; like the jangling of a piano that hasn't been tuned since before the war.

Article content

And why shouldn't she be uneasy, in the evening light, in this too-quiet Paris? Pedestrians with their heads down, cyclists slipping past. Her mind, like the city, is occupied.

Article content

Checkpoints. Shortages and queues. Occasionally, an outcry. People running. Soldiers with guns. Markets full of women trying to fill their children's woeful rations. A hand-painted sign. Yellow stars. A grandmother sitting on the pavement, her legs splayed, her hands empty, her gaze absent. Buses and trains rumble and smoke, carrying people away. Every moment, some piece of the city implodes and dies, leaving scar tissue.

The two women walking in front of Kit have painted their legs to look like stockings, with a careful seam drawn with grease pencil. They murmur to each other about practical things. Kit is one in a line of women, walking home late from work, as life carries on.

Her gaze breaks free, across the Rue de Clichy.

A woman is standing on the pavement, staring across the street, her arms at her sides.

She looks like Ivy -- no, she is Ivy.

It's impossible; Ivy is at home now, in England. But Kit knows her youngest sister's face. That defiant expression, the hint of a pout, like Betty Grable looking at a camera no one else can see. Every blonde curl pinned perfectly.

Kit's running across the road, yelling Ivy's name, trying to get her attention, when a bicycle screeches, its rider yells, and Kit, startled, sees the bicycle as it stops a few inches from her. People are staring at her, warily, wondering what she was running towards.

Because there is no one standing where she saw Ivy a moment ago. The figure of her sister is burned into her mind, like a negative image.

Kit looks all the way up and down that side of the street. Rooted, she turns in a circle, searching for her sister, until the cyclist tells her, not unkindly, to get out of the traffic, for the love of heaven. There is no one in the spot where Ivy was standing. No alley nearby, no store to duck into. A few steps to the south there's a massive apartment block, with a concierge standing just inside the door. He takes a long time before answering Kit's question, but eventually seems to decide that there's no harm in telling her that no, he did not just admit a young blonde woman. No one has entered for the last half-hour.

Back out in the evening light, she gathers herself. Whoever she saw, it must have been a stranger. Someone she mistook for Ivy. A trick of the mind.

Kit walks north towards her flat, the palm of one hand pressed to her temple.

It's the war, it's the damned war. Maybe it's the possibility of peace. Hope cracking all her defences like a weed in pavement.

Yesterday, the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy. The opening notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony have echoed in her mind, in the city's mind, all day. The notes that open the broadcasts of Radio Londres every night: three short and one long, Morse for the letter V, for victory. Then come the coded messages. And the news from the Free French in London, announcing that the long-expected invasion has begun. D-Day has come.

It's natural, to think about family at a time like this. To think of Ivy here. There must have been a hundred evenings when they walked together on this street, when Ivy, too, lived in Paris.

Kit trips over nothing and lurches forward, into the arms of a young German soldier, who calls her mademoiselle and asks if she is all right. The smell of his cologne, like rotten oranges, as she rights herself and gets her bearings. A sign in faded blackletter type dominates the Place de Clichy: Soldatenheim. The canteen for German soldiers. She usually gives the place a wide berth, but she was distracted. She picks her way through grey uniforms and smart skirts, through an obscene minefield of careful, light conversations.

Article content

Paris is a vacant museum, the void in every gilt frame stacked against the walls. Eyes of stone, like that sculpture of a nun's head she packed for sending away in the last days before the invasion, when the Louvre was being emptied. The mournful expression between stone wimple and stone chin-strap, the nose knocked off. Artist unknown. Not terribly interesting or unusual; but on that desperate day, it spoke to her, and she wrapped it in shredded cardboard and found a place for it in a crate full of precious things.

Everyone in the city has that mournful, absent expression in their eyes now. Eyes of stone would be a blessing. Nobody wants to see anything. But all the same, when she finally reaches her flat on the Rue des Dames she feels that she's being watched. Just the glare of the concierge. Dust motes swirl over the staircase in the last rays of the evening, filtered through a grimy window, as she climbs the three flights of stairs to her flat.

The familiar smell of yesterday's cabbage and her own cigarettes, a whiff of grease and metal from her bicycle by the door.

But something is wrong.

In the darkness, with one hand gripping the cold doorknob, she reaches a finger to the light switch. Nothing. No power, again. She stands very still, breathing shallow, letting her eyes adjust, interpreting the shadows.

In the far corner of the room, cigarette smoke rises into the moonlight from the window. She feels a twinge of disappointment at seeing the lithe silhouette and cloud of golden hair. No -- she's not disappointed to see her lover, just surprised. Evelyn Larsen hates Montmartre and hardly ever comes to Kit's flat. And they made no plans tonight.

Kit walks in and flops on to the sofa opposite.

"You're late, sweetheart," Evelyn says. She gives it an extra American drawl; she knows Kit thinks this makes her sound like a movie star. "You're too talented to be stuck in that basement with your files and pencils until sunset."

"I wouldn't have dawdled if I'd known you'd be here." She moves her leg to brush Evelyn's, in greeting. Unlike the women on the street, Evelyn has real stockings on her long and glorious calves.

"I had business in the neighbourhood, and curfew is coming."

Business. The German soldiers in the Place de Clichy; or perhaps at the Moulin Rouge. Every woman has to make her choices in Paris. Evelyn has always been honest with Kit about her choice to play the Germans for fools, to take her revenge in protection for her friends, in papers and useful information. But this transactional resistance -- if it even can be called resistance any more -- is not something Kit chooses to witness up close.

Is there even a way to get close to Evelyn Larsen? She seemed unapproachable when Kit met her on a dig in Yemen in 1937. Impossibly ethereal. Kit, on the other hand, always seemed to have sweaty armpits and trousers baggy at the knees.

Kit hated archaeology, as Father had always said she would. It was overwhelming, disorientating. She got headaches all the time, from the sun. Stubbornly, she stuck with it for months, until she finally admitted, in a letter to her friend Maxine, that she was miserable. Max said she was about to take a flat in Paris; why shouldn't Kit join her there for a while? Kit jumped at the chance to study art history at the École du Louvre, and get her bearings.

What a glorious moment, when Kit walked into Le Monocle in Paris the following year and saw Evelyn dancing with friends, saw her turn and smile, recognize her, call her by name.

How beautiful Evelyn was, but how beautiful everyone was then -- the girls with their high collars and tuxedos and sleek Marcel-waved hair. When the Occupation came, the club was boarded up; everyone knew what Nazis thought of inverts, and what they might do to a club full of them.

But Kit and Evelyn had something more in common. Evelyn was a private research assistant for an archaeologist in Paris, and Kit had taken a job at the Louvre as a research assistant to one of the experts on medieval sculpture. She and Evelyn had coffee, and then they had sex, and Evelyn said she was finding ways to help people however she could. She offered to get a letter through Vichy France to Kit's family, and for a year or so Kit was able to write to them, and to get letters back.

It has been several years, now, since the last letter. She does not know who is dead and who is alive. She has tried, very hard, to stop wondering. And she does not believe in ghosts.

Evelyn is looking at her with concern. "You're working too hard," she says.

Kit snorts. "Not hard enough. It's difficult to do one's research in an empty museum. I get the journal published every quarter, and I arrange my notes and files for my monograph, but I can't write it until I can get my hands on things. And of course, I do my part to placate the Nazis when they come. They always want to see the little we left behind when we got everything out in 1940."

Evelyn stubs out her cigarette. "About that. I wonder whether some of the items might be safer if they were returned to the Louvre now, what with the invasion in Normandy. What about the Bayeux Tapestry?"

Copyright © 2024 by Kate Heartfield

Reviews

There are currently no reviews for this novel. Be the first to submit one! You must be logged in to submit a review in the BookTrackr section above.

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details