Added By: Administrator

Last Updated: Administrator

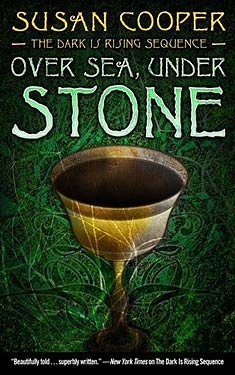

Over Sea, Under Stone

| Author: | Susan Cooper |

| Publisher: |

Simon Pulse, 2007 Puffin, 1968 Jonathan Cape, 1965 |

| Series: | The Dark is Rising: Book 1 |

|

1. Over Sea, Under Stone |

|

| Book Type: | Novel |

| Genre: | Fantasy |

| Sub-Genre Tags: | Juvenile Fantasy Mythic Fiction (Fantasy) Historical Fantasy |

| Awards: | |

| Lists: | |

| Links: |

|

| Avg Member Rating: |

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

"I DID NOT KNOW THAT YOU CHILDREN WOULD BE THE ONES TO FIND IT. OR WHAT DANGER YOU WOULD BE PUTTING YOURSELVES IN."

Throughout time, the forces of good and evil have battled continuously, maintaining the balance. Whenever evil forces grow too powerful, a champion of good is called to drive them back. Now, with evil's power rising and a champion yet to be found, three siblings find themselves at the center of a mystical war.

Jane, Simon, and Barney Drew have discovered an ancient text that reads of a legendary grail lost centuries ago. The grail is an object of great power, buried with a vital secret. As the Drews race against the forces of evil, they must piece together the text's clues to find the grail -- and keep its secret safe until a new champion rises.

Excerpt

CHAPTER ONE

WHERE IS HE?

Barney hopped from one foot to the other as he clambered down from the train, peering in vain through the white-faced crowds flooding eagerly to the St. Austell ticket barrier. "Oh, I can't see him. Is he there?"

"Of course he's there," Simon said, struggling to clutch the long canvas bundle of his father's fishing rods. "He said he'd meet us. With a car."

Behind them, the big diesel locomotive hooted like a giant owl, and the train began to move out.

"Stay where you are a minute," Father said, from a barricade of suitcases. "Merry won't vanish. Let people get clear."

Jane sniffed ecstatically. "I can smell the sea!"

"We're miles from the sea," Simon said loftily.

"I don't care. I can smell it."

"Trewissick's five miles from St. Austell, Great-Uncle Merry said."

"Oh, where is he?" Barney still jigged impatiently on the dusty grey platform, glaring at the disappearing backs that masked his view. Then suddenly he stood still, gazing downwards. "Hey--look."

They looked. He was staring at a large black suitcase among the forest of shuffling legs.

"What's so marvellous about that?" Jane said.

Then they saw that the suitcase had two brown pricked ears and a long waving brown tail. Its owner picked it up and moved away, and the dog which had been behind it was left standing there alone, looking up and down the platform. He was a long, rangy, lean dog, and where the sunlight shafted down on his coat it gleamed dark red.

Barney whistled, and held out his hand.

"Darling, no," said his mother plaintively, clutching at the bunch of paint-brushes that sprouted from her pocket like a tuft of celery.

But even before Barney whistled, the dog had begun trotting in their direction, swift and determined, as if he were recognizing old friends. He loped round them in a circle, raising his long red muzzle to each in turn, then stopped beside Jane, and licked her hand.

"Isn't he gorgeous?" Jane crouched beside him, and ruffled the long silky fur of his neck.

"Darling, be careful," Mother said. "He'll get left behind. He must belong to someone over there."

"I wish he belonged to us."

"So does he," Barney said. "Look."

He scratched the red head, and the dog gave a throaty half-bark of pleasure.

"No," Father said.

The crowds were thinning now, and through the barrier they could see clear blue sky out over the station yard.

"His name's on his collar," Jane said, still down beside the dog's neck. She fumbled with the silver tab on the heavy strap. "It says Rufus. And something else... Trewissick. Hey, he comes from the village!"

But as she looked up, suddenly the others were not there. She jumped to her feet and ran after them into the sunshine, seeing in an instant what they had seen: the towering familiar figure of Great-Uncle Merry, out in the yard, waiting for them.

They clustered round him, chattering like squirrels round the base of a tree. "Ah, there you are," he said casually, looking down at them from beneath his bristling white eyebrows with a slight smile.

"Cornwall's wonderful," Barney said, bubbling.

"You haven't seen it yet," said Great-Uncle Merry. "How are you, Ellen, my dear?" He bent and aimed a brief peck at Mother's cheek. He treated her always as though he had forgotten that she had grown up. Although he was not her real uncle, but only a friend of her father, he had been close to the family for so many years that it never occurred to them to wonder where he had come from in the first place.

Nobody knew very much about Great-Uncle Merry, and nobody ever quite dared to ask. He did not look in the least like his name. He was tall, and straight, with a lot of very thick, wild, white hair. In his grim brown face the nose curved fiercely, like a bent bow, and the eyes were deep-set and dark.

How old he was, nobody knew. "Old as the hills," Father said, and they felt, deep down, that this was probably right. There was something about Great-Uncle Merry that was like the hills, or the sea, or the sky; something ancient, but without age or end.

Always, wherever he was, unusual things seemed to happen. He would often disappear for a long time, and then suddenly come through the Drews' front door as if he had never been away, announcing that he had found a lost valley in South America, a Roman fortress in France, or a burned Viking ship buried on the English coast. The newspapers would publish enthusiastic stories of what he had done. But by the time the reporters came knocking at the door, Great-Uncle Merry would be gone, back to the dusty peace of the university where he taught. They would wake up one morning, go to call him for breakfast, and find that he was not there. And then they would hear no more of him until the next time, perhaps months later, that he appeared at the door. It hardly seemed possible that this summer, in the house he had rented for them in Trewissick, they would be with him in one place for four whole weeks.

The sunlight glinting on his white hair, Great-Uncle Merry scooped up their two biggest suitcases, one under each arm, and strode across the yard to a car.

"What d'you think of that?" he demanded proudly.

Following, they looked. It was a vast, battered estate car, with rusting mudguards and peeling paint, and mud caked on the hubs of the wheels. A wisp of steam curled up from the radiator.

"Smashing!" said Simon.

"Hmmmmmm," Mother said.

"Well, Merry," Father said cheerfully, "I hope you're well insured."

Great-Uncle Merry snorted. "Nonsense. Splendid vehicle. I hired her from a farmer. She'll hold us all, anyway. In you get."

Jane glanced regretfully back at the station entrance as she clambered in after the rest. The red-haired dog was standing on the pavement watching them, long pink tongue dangling over white teeth.

Great-Uncle Merry called: "Come on, Rufus."

"Oh!" Barney said in delight, as a flurry of long legs and wet muzzle shot through the door and knocked him sideways. "Does he belong to you?"

"Heaven forbid," Great-Uncle Merry said. "But I suppose he'll belong to you three for the next month. The captain couldn't take him abroad, so Rufus goes with the Grey House." He folded himself into the driving seat.

"The Grey House?" Simon said. "Is that what it's called? Why?"

"Wait and see."

The engine gave a hiccup and a roar, and then they were away. Through the streets and out of the town they thundered in the lurching car, until hedges took the place of houses; thick, wild hedges growing high and green as the road wound uphill, and behind them the grass sweeping up to the sky. And against the sky they saw nothing but lonely trees, stunted and bowed by the wind that blew from the sea, and yellow-grey outcrops of rock.

"There you are," Great-Uncle Merry shouted, over the noise. He turned his head and waved one arm away from the steering-wheel, so that Father moaned softly and hid his eyes. "Now you're in Cornwall. The real Cornwall. Logres is before you."

The clatter was too loud for anyone to call back.

"What's he mean, Logres?" demanded Jane.

Simon shook his head, and the dog licked his ear.

"He means the land of the West," Barney said unexpectedly, pushing back the forelock of fair hair that always tumbled over his eyes. "It's the old name for Cornwall. King Arthur's name."

Simon groaned. "I might have known."

Ever since he had learned to read, Barney's greatest heroes had been King Arthur and his knights. In his dreams he fought imaginary battles as a member of the Round Table, rescuing fair ladies and slaying false knights. He had been longing to come to the West Country; it gave him a strange feeling that he would in some way be coming home. He said, resentfully: "You wait. Great-Uncle Merry knows."

And then, after what seemed a long time, the hills gave way to the long blue line of the sea, and the village was before them.

Trewissick seemed to be sleeping beneath its grey, slate-tiled roofs, along the narrow winding streets down the hill. Silent behind their lace-curtained windows, the little square houses let the roar of the car bounce back from their whitewashed walls. Then Great-Uncle Merry swung the wheel round, and suddenly they were driving along the edge of the harbour, past water rippling and flashing golden in the afternoon sun. Sailing-dinghies bobbed at their moorings along the quay, and a whole row of the Cornish fishing boats that they had seen only in pictures painted by their mother years before: stocky workmanlike boats, each with a stubby mast and a small square engine-house in the stern.

Nets hung dark over the harbour walls, and a few fishermen, hefty, brown-faced men in long boots that reached their thighs, glanced up idly as the car passed. Two or three grinned at Great-Uncle Merry, and waved.

"Do they know you?" Simon said curiously.

But Great-Uncle Merry, who could become very deaf when he chose not to answer a question, only roared on along the road that curved up the hill, high over the other side of the harbour, and suddenly stopped. "Here we are," he said.

In the abrupt silence, their ears still numb from the thundering engine, they all turned from the sea to look at the other side of the road.

They saw a terrace of houses sloping sideways up the steep hill; and in the middle of them, rising up like a tower, one tall narrow house with three rows of windows and a gabled roof. A sombre house, painted dark-grey, with the door and windowframes shining white. The roof was slate-tiled, a high blue-grey arch facing out across the harbour to the sea.

"The Grey House," Great-Uncle Merry said.

They could smell a strangeness in the breeze that blew faintly on their faces down the hill; a beckoning smell of salt and seaweed and excitement.

As they unloaded suitcases from the car, with Rufus darting in excited frenzy through everyone's legs, Simon suddenly clutched Jane by the arm. "Gosh--look!"

He was looking out to sea, beyond the harbour mouth. Along his pointed finger, Jane saw the tall graceful triangle of a yacht under full sail, moving lazily in towards Trewissick.

"Pretty," she said, with only mild enthusiasm. She did not share Simon's passion for boats.

"She's a beauty. I wonder whose she is?" Simon stood watching, entranced. The yacht crept nearer, her sails beginning to flap; and then the tall white mainsail crumpled and dropped. They heard the rattle of rigging, very faint across the water, and the throaty cough of an engine.

"Mother says we can go down and look at the harbour before supper," Barney said, behind them. "Coming?"

"Course. Will Great-Uncle Merry come?"

"He's going to put the car away."

They set off down the road leading to the quay, beside a low grey wall with tufts of grass and pink valerian growing between its stones. In a few paces Jane found she had forgotten her handkerchief, and she ran back to retrieve it from the car. Scrabbling on the floor by the back seat, she glanced up and stared for a moment through the wind-screen, surprised.

Great-Uncle Merry, coming back towards the car from the Grey House, had suddenly stopped in his tracks in the middle of the road. He was gazing down at the sea; and she realised that he had caught sight of the yacht. What startled her was the expression on his face. Standing there like a craggy towering statue, he was frowning, fierce and intense, almost as if he were looking and listening with senses other than his eyes and ears. He could never look frightened, she thought, but this was the nearest thing to it that she had ever seen. Cautious, startled, alarmed... what was the matter with him? Was there something strange about the yacht?

Then he turned and went quickly back into the house, and Jane emerged thoughtfully from the car to follow the boys down the hill.

The harbour was almost deserted. The sun was hot on their faces, and they felt the warmth of the stone quayside strike at their feet through their sandal soles. In the center, in front of tall wooden warehouse doors, the quay jutted out square into the water, and a great heap of empty boxes towered above their heads. Three sea-gulls walked tolerantly to the edge, out of their way. Before them, a small forest of spars and ropes swayed; the tide was only half high, and the decks of the moored boats were down below the quayside, out of sight.

"Hey," Simon said, pointing through the harbour entrance. "That yacht's come in, look. Isn't she marvellous?"

The slim white boat sat at anchor beyond the harbour wall, protected from the open sea by the headland on which the Grey House stood.

Jane said: "Do you think there is anything odd about her?"

"Odd? Why should there be?"

"Oh--I don't know."

"Perhaps she belongs to the harbour-master," Barney said.

"Places this size don't have harbour-masters, you little fathead, only ports like Father went to in the navy."

"Oh yes they do, cleversticks, there's a little black door on the corner over there, marked Harbour-Master's Office." Barney hopped triumphantly up and down, and frightened a sea-gull away. It ran a few steps and then flew off, flapping low over the water and bleating into the distance.

"Oh well," Simon said amiably, shoving his hands in his pockets and standing with his legs apart, rocking on his heels, in his captain-on-the-bridge stance. "One up. Still, that boat must belong to someone pretty rich. You could cross the Channel in her, or even the Atlantic."

"Ugh," said Jane. She swam as well as anybody, but she was the only member of the Drew family who disliked the open sea. "Fancy crossing the Atlantic in a thing that size."

Simon grinned wickedly. "Smashing. Great big waves picking you up and bringing you down swoosh, everything falling about, pots and pans upsetting in the galley, and the deck going up and down, up and down--"

"You'll make her sick," Barney said calmly.

"Rubbish. On dry land, out here in the sun?"

"Yes, you will, she looks a bit green already. Look."

"I don't."

"Oh yes you do. I can't think why you weren't ill in the train like you usually are. Just think of those waves in the Atlantic, and the mast swaying about, and nobody with an appetite for their breakfast except me...."

"Oh shut up, I'm not going to listen"--and poor Jane turned and ran round the side of the mountain of fishysmelling boxes, which had probably been having more effect on her imagination than the thought of the sea.

"Girls!" said Simon cheerfully.

There was suddenly an ear-splitting crash from the other side of the boxes, a scream, and a noise of metal jingling on concrete. Simon and Barney gazed horrified at one another for a moment, and rushed round to the other side.

Jane was lying on the ground with a bicycle on top of her, its front wheel still spinning round. A tall dark-haired boy lay sprawled across the quay not far away. A box of tins and packets of food had spilled from the bicycle carrier, and milk was trickling in a white puddle from a broken bottle splintered glittering in the sun.

The boy scrambled to his feet, glaring at Jane. He was all in navy-blue, his trousers tucked into Wellington boots; he had a short, thick neck and a strangely flat face, twisted now with ill temper.

"Look where 'ee's goin', can't 'ee?" he snarled, the Cornish accent made ugly by anger. "Git outa me way."

He jerked the bicycle upright, taking no heed of Jane; the pedal caught her ankle and she winced with pain.

"It wasn't my fault," she said, with some spirit. "You came rushing up without looking where you were going."

Barney crossed to her in silence and helped her to her feet. The boy sullenly began picking up his spilled tins and slamming them back into the box. Jane picked one up to help. But as she reached it towards the box the boy knocked her hand away, sending the tin spinning across the quay.

"Leave 'n alone," he growled.

"Look here," Simon said indignantly, "there's no need for that."

"Shut y' mouth," said the boy shortly, without even looking up.

"Shut your own," Simon said belligerently.

"Oh Simon, don't," Jane said unhappily. "If he wants to be beastly let him." Her leg was stinging viciously, and blood trickled down from a graze on her knee. Simon looked at her flushed face, hearing the strain in her voice. He bit his lip.

The boy pushed his bicycle to lean against the pile of boxes, scowling at Barney as he jumped nervously out of the way; then rage suddenly snarled out of him again. "--off, the lot of 'ee," he snapped; they had never heard the word he used, but the tone was unmistakable, and Simon went hot with resentment and clenched his fists to lunge forward. But Jane clutched him back, and the boy moved quickly to the edge of the quay and climbed down over the edge, facing them, the box of groceries in his arms. They heard a thumping, clattering noise, and looking over the edge they saw him lurching about in a rowing-dinghy. He untied its mooring-rope from a ring in the wall and began edging out through the other boats into the open harbour, standing up with one oar thrust down over the stern. Moving hastily and angrily, he clouted the dinghy hard against the side of one of the big fishing-boats, but took no notice. Soon he was out in open water, sculling rapidly, one-handed, and glaring back at them in sneering contempt.

As he did so they heard a clatter of feet moving rapidly over hollow wood from inside the injured fishing-boat. A small, wizened figure popped up suddenly from a hatch in the deck and waved its arms about in fury, shouting over the water towards the boy in a surprisingly deep voice.

The boy deliberately turned his back, still sculling, and the dinghy disappeared outside the harbour entrance, round the jutting wall.

The little man shook his fist, then turned towards the quay, leaping neatly from the deck of one boat to another, until he reached the ladder in the wall and climbed up by the children's feet. He wore the inevitable navy-blue jersey and trousers, with long boots reaching up his legs.

"Clumsy young limb, that Bill 'Oover," he said crossly. "Wait'll I catch 'n, that's all, just wait."

Then he seemed to realise that the children were more than just part of the quay. He grunted, flashing a quick glance at their tense faces, and the blood on Jane's knee. "Thought I heard voices from below," he said, more gently. "You been 'avin' trouble with 'n?" He jerked his head out to sea.

"He knocked my sister over with his bike," Simon said indignantly. "It was my fault really, I made her run into him, but he was beastly rude and he bashed Jane's hand away and--and then he went off before I could hit him," he ended lamely.

The old fisherman smiled at them. "Ah well, don't 'ee take no count of 'n. He'm a bad lot, that lad, evil-tempered as they come and evil-minded with ut. You keep away from 'n."

"We shall," Jane said with feeling, rubbing her leg gingerly.

The fisherman clicked his tongue. "That's a nasty old cut you got there, midear, you want to go and get 'n washed up. You'm on holiday here, I dessay."

"We're staying in the Grey House," Simon said. "Up there on the hill."

The fisherman glanced at him quickly, a flicker of interest passing over the impassive brown wrinkled face. "Are 'ee, then? I wonder maybe"--then he stopped short, strangely, as if he were quickly changing his mind about what he had been going to say. Simon, puzzled, waited for him to go on. But Barney, who had not been listening, turned round from where he had been peering over the edge of the quay.

"Is that your boat out there?"

The fisherman looked at him, half taken aback and half amused, as he would have looked at some small unexpected animal that barked. "That's right, me 'andsome. The one I just come off."

"Don't the other fishermen mind you jumping over their boats?"

The old man laughed, a cheerful rusty noise. "I'd'n no other way to get ashore from there. Nobody minds you comin' across their boat, so long's you don't mark 'er."

"Are you going out fishing?"

"Not for a while, midear," said the fisherman amiably, pulling a piece of dirty rag from his pocket and scrubbing at the oil-marks on his hands. "Go out with sundown, we do, and come back with the dawn."

Barney beamed. "I shall get up early and watch you come in."

"Believe that when I see 'n," said the fisherman with a twinkle. "Now look, you run and take your little sister home and wash that leg, don't know what scales and muck have got into it off here." He scuffed at the quay with his glistening boot.

"Yes, come on, Jane," Simon said. He took one more look out at the quiet line of boats; then put up his hand to peer into the sun. "I say, that oaf with the bicycle, he's going on board the yacht!"

Jane and Barney looked.

Out beyond the far harbour wall, a dark shape was bobbing against the long white hull of the silent yacht. They could just see the boy climbing up the side, and two figures meeting him on the deck. Then all three disappeared, and the boat lay deserted again.

"Ah," said the fisherman. "So that's it. Young Bill were buying stores and petrol and all, yesterday, enough for a navy, but nobody couldn't get it out of him who they was for. Tidy old boat, that'n--cruisin', I suppose. Can't see what he made all the mystery about."

He began to walk along the quay: a rolling small figure with the folded tops of his boots slapping his legs at every step. Barney trotted beside him, talking earnestly, and rejoined the others at the corner as the old man, waving to them, turned off towards the village.

"His name's Mr. Penhallow, and his boat's called the White Heather. He says they got a hundred stone of pilchard last night, and they'll get more tomorrow because it's going to rain."

"One day you'll ask too many questions," said Jane.

"Rain?" said Simon incredulously, looking up at the blue sky.

"That's what he said."

"Rubbish. He must be nuts."

"I bet he's right. Fishermen always know things, specially Cornish fishermen. You ask Great-Uncle Merry."

But Great-Uncle Merry, when they sat down to their first supper in the Grey House, was not there; only their parents, and the beaming red-cheeked village woman, Mrs. Palk, who was to come in every day to help with the cooking and cleaning. Great-Uncle Merry had gone away.

"He must have said something," Jane said.

Father shrugged. "Not really. He just muttered about having to go and look for something and roared off in the car like a thunderbolt."

"But we've only just got here," Simon said, hurt.

"Never mind," Mother said comfortably. "You know what he is. He'll be back in his own good time."

Barney gazed dreamily at the Cornish pasties Mrs. Palk had made for their supper. "He's gone on a quest. He might take years and years. You can search and search, on a quest, and in the end you may never get there at all."

"Quest my foot," Simon said irritably. "He's just gone chasing after some stupid old tomb in a church, or something. Why couldn't he have told us?"

"I expect he'll be back in the morning," Jane said. She looked out of the window, across the low grey wall edging the road. The light was beginning to die, and as the sun sank behind their headland the sea was turning to a dark grey-green, and slow mist creeping into the harbour. Through the growing haze she saw a dim shape move, down on the water, and above it a brief flash of light; first a red pinprick in the gloom, and then a green, and white points of light above both. And she sat up suddenly as she realised that what she could see was the mysterious white yacht, moving out of Trewissick harbour as silently and strangely as it had come.

Copyright © 1965 by Susan Cooper

Reviews

Images

No alternate cover images currently exist for this novel.

Full Details

Full Details