![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

12/25/2015

![]()

Abandon all hope... she's reviewing another NivPourn book.

A comedy: less divine, more contrapasso. Perhaps a small penance for those bloggers who make fun of old classics, including that awesome time-travel story you loved when you were eleven and haven't the social-awareness and maturity to admit to the shortcomings of things you enjoy. I'm sure I had it coming.

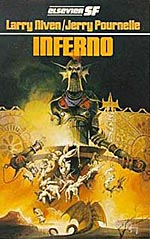

In Inferno, Larry and Jerry's 1975 novel serialized in Galaxy, science fiction writer Allen Carpenter (Jesus reference! Jesus reference!) dies after a drunken fall at a science fiction convention. He recovers to find himself in a timeless void until his guide, some guy named Benito, rescues him from a bottle and takes him through the vestibule and into the ten circles of Hell. The rational, agnostic Carpenter prefers to think he's in a far-future theme park called Infernoland. Modeled off of Dante Alighieri's Inferno and C.S. Lewis' The Great Divorce, Niven and Pournelle parody the pedantic mindset of the Hard sci-fi writer.

But, when even Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle are surprised by the success of one of their books, you know you have stumbled upon an INSIGNIFICANT MOMENT OF GENRE HISTORYYYYY.

It's not LOL funny, or even lol funny, but the premise is clever in its self-deprecating way. Niven and Pournelle cast their hero as a hyper-rational ego who can't see the truth for gears. Where we see a giant demon, Carpenter sees an engineered machine, and not even Benito Mussolini or Clarke's Law can fully convince him otherwise. (Now why Benito Mussolini was chosen as an adequate stand-in for Virgil, I don't know...) And, although ad execs and bureaucracy in hell are nothing new in fiction, the gnats are a nice touch. I'll give Larry and Jerry that.

Typical of NivPourn stories, though,Inferno is peppered with old-fashionedy grandpa assumptions about women and gay men--not nearly so bad as The Mote in God's Eye, thank goodness, but the F-bomb is dropped a few times, and I don't mean 'fuck.' Worse, though, it's an insubstantial read, a funny joke that ran out of steam long before that second beer, and the substandard NivPourn prose shows itself to be just what it is: a careless slinging of ideas across the page, check please.

What do I mean? Let's have a look at examples of The Void in fiction:

Here's Dante Alighieri's version, Hell's vestibule (Sibbald trans. 1884)

Scarce know I how I entered on that ground,

So deeply, at the moment when I passed

From the right way, was I in slumber drowned.

But when beneath a hill arrived at last,

Which for the boundary of the valley stood,

I upwards looked and saw its shoulders glowed,

Radiant already with that planet's light

Which guideth surely upon every road.

A little then was quieted by the sight

The fear which deep within my heart has lain

Through all my sore experience of the night

And as the man, who, breathing short in pain,

Hath 'scaped the sea and struggled to the shore,

Turns back to gaze upon the perilous main;

Even so my soul which fear still forward bore

Turned to review the pass when I egressed,

And which non, living, ever left before.

My wearied frame refreshed with scanty rest,

I to ascend the lonely hill essayed;

The lower foot still that on which I pressed. (10-30)

Not that I would ever expect or want a genre writer to parrot the style of a medieval poet. So let's take a look at Philip K. Dick, not always the best writer, but this portrayal of emptiness--not in Hell, but in a dusty, old, post-nuke apartment complex-- successfully evokes a powerful sense of void in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep:

Silence. It flashed from the woodwork and the walls; it smote him with an awful, total power, as if generated by a vast mill. It rose from the floor, up out of the tattered gray wall-to-wall carpeting. It unleashed itself from the broken and semi-broken appliances in the kitchen, the dead machines which hadn't worked in all the time Isidore had lived here. From the useless pole lamp in the living room it oozed out, meshing with the empty and wordless descent of itself from the fly-specked ceiling. It managed in fact to emerge from every object within his range of vision, as if it--the silence--meant to supplant all things tangible. Hence it assailed not only his ears but his eyes; as he stood by the inert TV set he experience the silence as visible and, in its own way, alive. Alive! He had often felt its austere approach before; when it came, it burst in without subtlety, evidently unable to wait. The silence of the world could not rein back its greed. Not any longer. Not when it had virtually won. (20)

Now here is Niven and Pournelle trying to portray a similar sense of unbearable vacuum:

I couldn't tell how long I was there. There was no sense of time passing. I screamed a lot. I ran nowhere forever, to no purpose: I couldn't run out of breath, I never reached a wall. I wrote novels, dozens of them in my head, with no way to write them down. I relived that last convention party a thousand times. I played games with myself. I remembered every detail of my life, with a brutal honesty I'd never had before; what else could I do? All through it, I was terrified of going mad, and then I'd fight the terror, because that could drive me mad--

I think I did not go mad. But it went on, and on, and on, until I was screaming again (15-16).

That's the most visceral passage in the novel.

A juvenile read with a first-page punchline, it's meh-funny, but not that funny, and only on one level, really. Granted, it's not intended to be deep, but, while I appreciate Niven and Pournelle's good humor about themselves in relation to their work, that's just not enough to last 100 pages beyond what should have been a one-off short story.

Like the Hell of NivPourn's invention, Inferno is not that horrible, but it's not very good, either. Let's put this one in Limbo.

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com