![]() couchtomoon

couchtomoon

3/10/2015

![]()

Happy and angry. Happily angry. Everything, all at once. That's life, boy. You just keep getting fuller, until you burst and Allah takes you and casts your soul into another life later on. And so everything just keeps getting fuller. [290]

Two souls, Happy and Angry. The Monkey and the Lion. Their fates intertwined, reincarnate to new lands, always to rediscover one another, always to redefine their relationship, and, most importantly, to drive history forward.

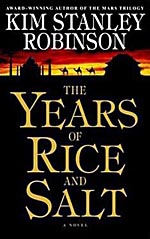

At its most basic: a constructivist reimagining of the history of the world, this time without the White people. Its plot structure: a story about the pursuit of enlightenment and self-actualization for a jati trapped together by their fates. A literal revision of history, if fate could take the pink end of a pencil and erase European history since the Black Plague: the wars, the genocides, the subjugations, the oppression, the hegemony, the privilege, the "When is International White Man's Day?"

None of those things go away entirely. Robinson won't play those games. As evidenced by his stunning Mars trilogy, Robinson writes utopian realism, not utopian fantasy, and The Years of Rice and Salt proves consistent with its implementation of progressive characters with progressive ideas, but with flaws, backfires, and struggles. But history happens differently, better, with the sensibilities of non-White cultures shaping its progress. True to form, the story adopts a non-Western structure, a meandering tale with a pageant of characters who parade through history in various manifestations, even in death.

Robinson also plays with symbolism. Scenes in the bardo, a sort of pre-reincarnation limbo, as well as other recurring metaphors, such as a literal Easter egg, divulge much about Robinson's theory of history and civilization. The Happy character is adaptation. The Angry character is rage against the hands that write history. They both resent and sometimes rebel against the bardo gods and goddesses, who represent ideas of fate, dharma, caste, "The Great Man" premise and all its trappings. The Angry character smashes up the bardo in one scene, only to be condemned to the life of a lioness in the next tale.

By alternating each tale with scenes of reality and limbo, Robinson begs the question: Who impacts history? His characters certainly try. With each life, the idea of fate is forgotten... until the next bardo scene. Their powerlessness is reinforced. More Anger. "Forget about him, forget about the gods. Let's concentrate on doing it ourselves. We can make our own world." [352].

Things that are different in this world: Europe (Firanja) becomes an exile for liberal Islamic thinkers, where feminist and revisionist thought is championed. The New World explored by the Chinese, and the Inka die out from the violent contact. Northern Native Americans (Hodenosaunee) barely survive the cultural collision, but unite as a collaborative league, and become an important mediator in the delicate balance of power that exists between Dar al-Islam and the Chinese empire. We meet the Marx, the Wollstonecraft, the Einstein of this timeline; they exercise more fire and caution this time around.

Always timely, Robinson wrote the majority of the book prior to, and published just six months after the bombing of the World Trade Center, yet it feels GWOT-inspired. Although Robinson's Buddhist preferences are clear within the narrative, he takes pains to remind us of the non-dogmatic nature of Islam, as "Islam was an intellectual discipline..." [257] and "Allah appears to like mathematics..." [276], among many moments when Islamic scientists temper extremist thought and technological advancement.

With the history of the world on the cutting board, some omissions are glaring. Still subjugated and enslaved, no part of Africa rises as an effective contributing world power. With many Jewish people wiped out in the plague, the surviving numbers are barely mentioned and have no influence in this world. Some revisions seem odd. Through his characters, Robinson posits some curious theories, including a theory that the abstract structure of Arabic languages nurtures extremist thought, due to a lack of empathic perspective.

Additionally problematic, the continuity of characters from life to life is often difficult to recognize. (There is a code, but I didn't recognize it until the novel was nearly over.) Characters' stories often end abruptly, and without resolution. Each narrative feels unresolved. But that's the way history goes.

Why read on? Why pick up their books from the far wall where it has been thrown away in disgust and pain, and read on? Why submit to such cruelty, such bad karma, such bad plotting?

The reason is simple: these things happened. [349]

Another case of a liberal science fiction writer hanging his socialist beliefs on the framework of a narrative. Another case of a tale that exists only for the sake of the ideas it contains. Another case of a white author appropriating the stories of nonwhite cultures to atone for his own white guilt.

Yes, this book will bother people. But it's done respectfully, skeptically, thoroughly, and earnestly. And the realism that Robinson provides gives the feeling that this is history as it should have happened.

Perhaps we are the timeline gone wrong.

To be human is easy, to live a human life is hard; to desire to be human a second time is even harder. If you want release from the wheel, persevere. [390]

http://couchtomoon.wordpress.com